Making a tune is now as easy as taking a photo and uploading it to Instagram. With its 1 billion monthly active users, Instagram has made photographers out of all us. As phone cameras improved, the Instagram filters did the rest. Music has spent most of this century battling the ghosts of piracy. The major labels first reinvented themselves as licensing models, using the IP in their catalogues to generate revenues that has propelled them back to pre-Napster times. More recently, everybody in the industry has become a digital media company: Warner invests heavily in gaming, musicians like Rihanna and Jay Z build out their brands far beyond music, and every indie artist has to navigate the digital world from social media to direct-to-fan strategies. Alongside these developments music creator tools proliferate. From Myspace to Soundcloud and now TikTok, sharing and discovering music has undergone changes in relation to the underlying medium. Each new medium led to new structures in pop music. Now, the next step is that everyone can become a music creator and it won’t be long before we see a medium where we consume music as readily as we adapted our thumbs to scroll through miles of photographic content each year.

Creator tools

In November 2020 MIDiA Research already claimed that creator tools were the present of the music industry. They showed that there were 14.6 million music creators using apps and platforms like YouTube and Soundcloud, but also Vampr, Bandlab, Loopcloud, Splice, Boomy, and many more.

These tools range from a focus on distribution to collaboration and various stages of production like loops, mastering, and effect. If you look to collaborate in real time, you can. If you want to easily get your track mastered there’s no need to go to a studio. If you need a specific sound, there’s now any number of sample libraries you can turn to.

That number of 14.6 million calculated by MIDiA is sure to have grown in the past year. Similar to the number of tracks released on the streaming services, roughly 60,000 per day back in February, which will also keep increasing. If you look at an app like Bandlab, you see the potential wave of content generated through creator tools: users create 11 million tracks each month. That’s the total number of tracks released to streaming services over a period of 6 months. In other words, not all of those tracks are released. As these numbers continue to grow, the music industry will need to change to adapt.

How to stand out from the crowd? Or should you even aspire to it?

It’s already difficult to make sure you get your new track heard when you are one of 60,000. If you are an indie you may never get the chance to make it onto those New Music Friday playlists. A study released earlier this year shows how “independent label artists are getting far less than their fair share of access to the most popular playlists.” This kind of issue underlines the current power structures in music. But if we transpose the number of tracks currently released on Bandlab in a month to the DSP format, it could well be that that whole system would simply break down. Moreover, if we take the step to consider a billion music creators using an app like Bandlab each month the volume of created music would be close to unimaginable.

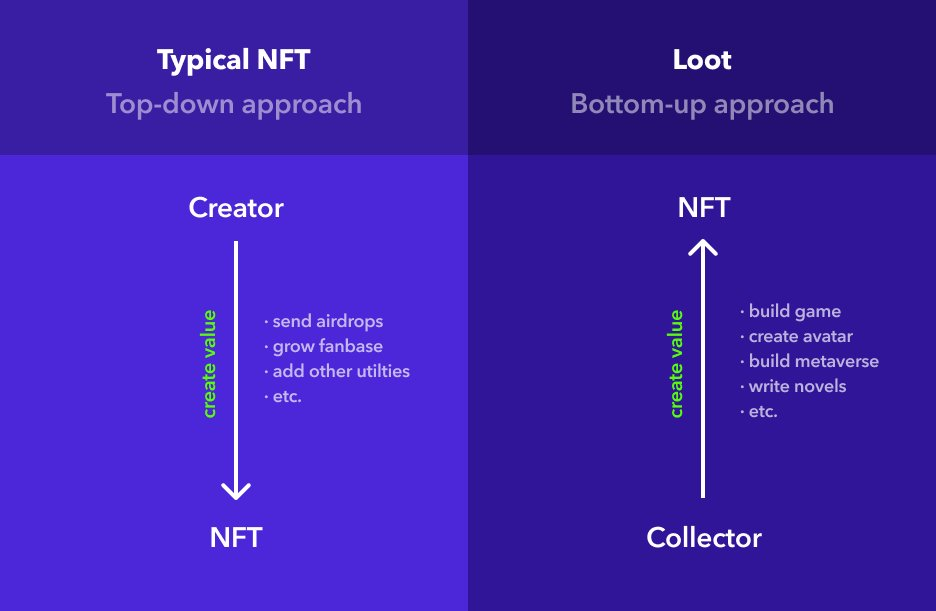

In a way, this is happening already. TikTok has more than one billion video views each day, and most of those include music. Snap, through it’s acquisition of Voisey, now has millions of users creating tracks each day to add to their snaps. And yet, there’s no dedicated medium for music yet that has attracted these one billion MAUs. Once we get there, though, it won’t be about standing out from the crowd of recorded music anymore. Instead, each creator will be subject to the same things anyone on a current social media-platform is: algorithms and community. It’s in the latter that we may see a different effect of music growing to the size of photography.

Since music is inherently collaborative, it means that all those creator tools also have these features built into them. Some of them in a very direct way, such as Vampr, others more indirectly, like Splice. But any medium looking to tap into people’s deep-seated desires for making music will have to build to cater to niches. As content will get churned out at an ever greater number people will find each other in shared loves of musical nooks and crannies and find ways to express their identities in relation to that.

Existential fright

Going back to the comparison with Instagram and photography we can use the development of commentary on the medium and digital photography more broadly to sketch responses to a billion music creators. 10 years ago the journalist and artist Chris Wiley wrote that:

“It is indisputable that we now inhabit a world thoroughly mediatized by and glutted with the photographic image and its digital doppelganger. Everything and everyone on earth and beyond, it would seem, has been slotted somewhere in a rapacious, ever-expanding Borgesian library of representation that we have built for ourselves. As a result, the possibility of making a photograph that can stake a claim to originality or affect has been radically called into question.”

So, in a way we’re moving into a world that’s thoroughly mediatized by the sonic in the form of melodies, beats, hooks. Some of these put together by people calling themselves artists, others by people who quickly threw together a few loops. The former might be looking to make a living from their art. The latter might just be enjoying themselves and have no ambition to share their creations beyond a few friends and like-minded people. The question of originality remains pertinent.

That question, however, isn’t new to this situation. Pop music simply doesn’t exist beyond a limited number of chords. And we’ve seen it before, of course. The advent of radio was thought to kill live music consumption – it didn’t. TV was then the death of radio – instead radio revenues increased. The music video would then kill the radio star – radio revenues increased again. The internet doomed the recorded music industry – and piracy had a serious impact, but revenues are now back to where they were 20 years ago. With each new medium, each new iteration of distribution, musicians kept creating and finding audiences.

Final note

Just as smart-phone cameras and Instagram filters have influenced a generation of photographers, so will the current boom of creator tools shape the sound of music for the next decade or so. It’s simply not necessary anymore to have any musical training in order to create music. Apps like Boomy allow everyone to play around intuitively and create sounds that feel like music. Similarly, Bandlab has a loop feature that allows anyone to create something with a pleasant enough melody. Should that lead to existential questions about what music is? Probably not. Instead, we would do well to focus on new niches popping up around shared interests in certain stems, riffs, drum rolls, etc. We may look at and listen to music differently if everyone can make it, but we won’t enjoy it less.