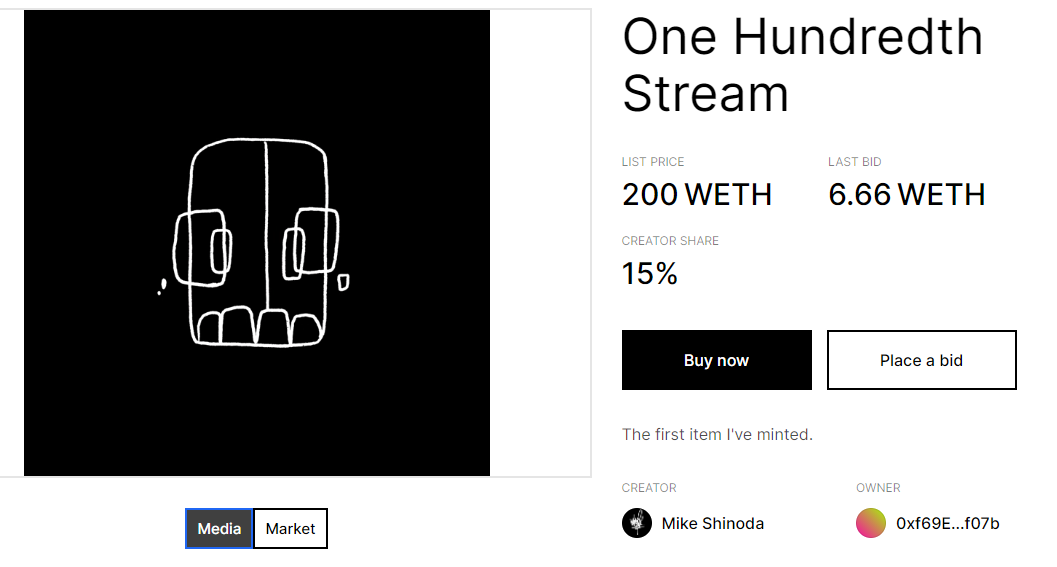

Linkin Park‘s Mike Shinoda just sold a digital piece of art for $30.000 and took to Twitter explaining some of this thoughts in a thread:

“Even if I upload the full version of the contained song to DSPs worldwide (which I can still do), i would never get even close to $10k, after fees by DSPs, label, marketing, etc.”

The ownership of this piece of art is tracked through a non-fungible token on a blockchain. Blockchains are commonly used as distributed ledgers: databases operated by networks of users, like Ethereum. They keep records of any changes to the ledger and can track things like ownership of tokens or cryptocurrency, e.g. Bitcoin.

But so what if a piece of art is recorded into a distributed database? Why the hype?

The current cultural moment is strongly influenced by the pandemic. Artists saw a big drop in income. Streaming revenue isn’t cutting it for most. So the big experimentation began. Artists searched for revenue through things like livestreaming, fan clubs, ticketed virtual meet & greets, online courses, and NFT auctions…

Why are people buying content that can easily be duplicated?

Many a music industry conference panel has bemoaned the fact that people are willing to buy a cup of coffee or bottle of water, but won’t spend that money on a download and instead chose to pirate it (in the days long before Spotify counted 150M paying subscribers). Two decades later and many of the same philosophical debates about the price and value of music continue. Meanwhile, gaming, an industry that faced the same piracy issues as the music industry, pragmatically pioneered ways to get people to pay for completely virtual items.

Gaming gave the ownership of virtual items a valuable context. People who spent many hours a week inside games would find value in virtual real estate or vanity items that translates into real world currency. This is not something recent. In 2013, someone paid $38,000 for an in-game item in Dota2 – an item which doesn’t improve a player’s performance, but just makes them look cooler. In 2010, virtual real estate by the name of Club Neverdie in online game Entropia sold for $635,000.

Now, ten years later, we’re seeing the same dynamic emerge for music. Owning an NFT doesn’t necessarily mean that nobody else can enjoy the work of art associated with the token, much like with physical art that’s exhibited. With the emerging metaverse, some are expecting NFTs to become its property rights.

It works like an auction; the value is determined by the bidders. At the end, one person gets the NFT. Think of it like like owning a 1 of a kind item in a game, or like “owning” an instagram post. It’s a weird thing to own, yes, but:

— Mike Shinoda (@mikeshinoda) February 6, 2021

(more)

NFT x Metaverse

The idea of the metaverse essentially boils down to a virtual shared space. One prominent example of this concept is Roblox, which is a gaming platform in which people can build their own experiences that are all interconnected through Roblox’ economy (its currency being Robux). Another is Fortnite, which has some of the ingredients already, but hasn’t yet developed a marketplace with low barriers to entry like Roblox has. Despite that, one of the best primers on the topic of the metaverse is the below interview with Tim Sweeney, CEO of Epic Games, which owns Fortnite.

It’s the convergence of various pandemic-accelerated trends (VR / XR, virtual economies, crypto) and the expectations of people in these domains that is currently driving NFT art’s success stories ($750,000 CryptoPunk sale, Panther Modern‘s $666 sale, virtual critters for $100,000 a piece). If you want to know what the future holds, look at what the smartest people in the room are doing, because they’ll be the ones building that future.

12 years after the initial release of Bitcoin and the world’s introduction to blockchain, crypto is starting to emerge as an anticipated layer of connectivity for transactions occurring in the metaverse. With a market cap higher than Facebook at the time of writing, Bitcoin has made many early adopters very rich (as have other cryptocurrencies). Besides figuring out how to build an infrastructure in which they can effectively use their blockchain-riches, we’re seeing this money flow into other spaces, like art (and soon Tesla).

Simplified: to understand some of NFTs’ success, you should look at the crypto space as a metaverse without an interface that looks like a video game. The participants of that space are still players: they’re building their own world, their own infrastructure. They care about what they look like in that world, just like how people in virtual worlds care enough about their looks that they’re willing to buy in-game currencies like Robux (to the sum of billions of USD in 2020). Owning art is cool – it gives you standing in your micro-community which is part of larger meta-communities (e.g. a gaming clan is a community inside the community of one server of a game, which is a community inside the global player-base of that game).

And sure, there’s altruism too, because it’s cool to support art. However counting on altruism tends to spawn panel discussions to compare bottles of water to digital art. Focus on non-altruistic value.

Lastly, regarding the game item or IG post comparison: it doesn’t matter if you think a current bidding price is too high for a digital collectible. It matters that one person thinks the the price is worth it.

— Mike Shinoda (@mikeshinoda) February 6, 2021

(more)