I spent the last week living from an Airbnb while getting started with my new job at IDAGIO in Berlin. Down the street from my Airbnb was a cheap Vietnamese place, where I ate a couple of times. They always had Vietnamese pop music on, but one day they had a CD by a Vietnamese singer covering Western pop songs. In English. I thought about it for a little: why wouldn’t they just play the originals?

These cover releases are often financially motivated, but since the restaurant has to pay some collection society, and a Spotify subscription gives you all the music for just $10, I figured that the reason for this music playing was probably not something financial.

I then wondered: could it be that they simply have more of a connection to the Vietnamese performer, and prefer to hear these works from his mouth?

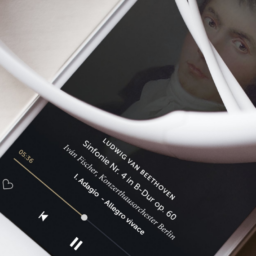

I’ve been getting into a new way of thinking about music by stepping into classical. Suddenly, there’s not 1 original and then some ‘lesser’ remixes and covers. There’s a composition, with the author of that work often having deceased before modern recording technology, and then there are countless recordings of performances of that work. Sometimes there’s an relatively undisputed ‘best’, but often it comes down to personal taste, preference, and opinion.

In the last century, music went through an enormous change. It went from ‘folk’ to ‘pop’. Here’s what I mean with each phrase:

- Folk: music that’s not ‘owned’ by a single individual or corporation, but rather by the culture in which it was born. A song is not necessarily known for a particular performer, but instead is performed by many performers: ones that reach success far and wide, as well as local performers who just like to sing in front of a crowd in evenings or weekends.

- Pop: music that’s controlled and owned. Songs are known for their original version and original performers. In this sense, the meaning extends beyond the charts, and into modern day underground rock, metal, and to a certain extent hiphop and dance music.

Recording technology in the 20th century brought about a transition: where once music was ‘folk’ by default, it became ‘pop’ instead. The rise of mass consumerism and cheap global distribution decreased the amount of time a song needed to spread geographically. These was now also a default version through which basically everyone became familiar with the work, rather than through their local performer or traveling bands.

While this system has generated a vast amount of money, and a huge music economy, I also think that music as an experience has lost a lot through this. People’s relationships with works are more superficial and performers are less incentivized to be the best performer of a certain work, since they can basically be the only one.

Back to the Vietnamese restaurant.

I got to thinking: what if we can ‘folk-ify’ modern pop music. It’s already being done to a certain extent. The remix culture on Soundcloud is a great example of it, and so is the cover culture on YouTube. What if the way we’re structuring the navigation in content on IDAGIO (such as: composers > works > recordings and performers) some day could become relevant for ‘pop’?

It would mean people would be able to browse based on songwriter, and then see all the pop songs related to that writer. They’d then be able to explore each song, and all the performances of it. They could sort by proximity: either offline (geographic), or online (based on your social graph and digital footprint). This could make the performance they listen to more personally relevant, just like the CD in the Vietnamese restaurant is to the owners of the restaurant.

It could make music more participative, and in a way it already is becoming so: YouTube, Soundcloud, remix apps, democratization of production tools, cheap hardware for recording (like our phones), Musical.ly, performances on livestream… The two most remix-heavy genres we know, dance and hiphop, are the ones most influential to the millennial demographic and younger. Both house and hiphop were born of affordable drum computers and samplers, of looping existing records, reinterpreting them, creating a new performance out of something that already existed.

The hard part has always been incentivizing the rights holders. Just look at the lawsuits.

We’re reaching an interesting time: we’re getting very good at interpreting really large datasets. Machine learning and AI are set to revolutionize our every day existence in just a few years. Then there’s blockchain, which is a good technology for tracking the complexity involved with a very nested type of ownership if we indeed ‘folk-ify’ pop music (without radically overhauling modern notions of intellectual property).

Music doesn’t have to become more participative, but it can. I think there’s a good economic case for it, but it still needs to be the product of deliberate choice of individuals. People in government can look at funding music education, and modernizing it, because the computer is the most important instrument for our generation (I know some of you will strongly disagree: find me at Midem, Sonár+D, or c/o pop and we can discuss over a beer). Musicians can think of how they can invite fans to contribute or interact with their music. People with entrepreneurial mindsets can think about solving some of the issues related to rights, or look at how musicians can monetize this type of interactivity.

And we all, as listeners, simply need to do one thing more often: sing.