This week I’ll be speaking about ethics & web3 at an event hosted by JUMP, an accelerator for the European music market. While I’ll make sure to dive into topics like energy use, economic inclusion and the tyranny of structurelessness, the invitation also got me thinking about how the web3 provides more ethical frameworks for our networked future.

Networked reality

First, back to fundamentals. We live in a networked reality. This is different from the channel reality of mass media before the internet. Messages and information traveled through channels, linearly or bi-directionally, through media but also distribution channels in the case of physical information carriers (e.g. CDs). It wasn’t piracy that was the real shock to the music industry: it was the transition from channel reality to network reality.

Networked reality implies data can travel freely through networks. Memes are an important part of the culture that has emerged from these networks. The remix is the internet’s language.

This networked reality initially played out in a rather decentralized way across loosely connected communities running their own software (e.g. vBulletin or phpBB forums). Network also means network effects and social platforms soon started leveraging their user activity to attract more users — slowly walling off data that had been accessible without an account through APIs or public pages. This created an extractive economy in which the value created by people funnels upwards to the platform owners. Eventually, the platform economy established a near-monopoly over the internet’s social layer.

This established certain platforms as de facto public infrastructure. Think about it this way: when you step outside your front door in real life, chances are you step out onto public infrastructure, free to use, paid for by taxes, and governed by democratically elected bodies. When you step outside your front door virtually, you move immediately into private infrastructure, paid for by ads and your data, and governed by non-democratic hierarchies. For many people, it’s unthinkable to cut ties with friends and family and abandon WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, Telegram, Line, WeChat, Twitter, etc. It would feel to them like the virtual equivalent of moving away into the forest and becoming a hermit.

Networked reality has become a platform reality. Economically almost more akin to the channel reality of mass media than the distributed nature of the early web. One could espouse the merits of all the free-to-use tools, but the reality is that their dynamics are extractive. As the adage goes: if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. Entire books could be written (and indeed have) about how we got here. I want to focus this piece on how web3 offers a more ethical way forward.

Your book and article recommendations on this topic are welcome in the comments.

Web3: returning ethics to networked reality

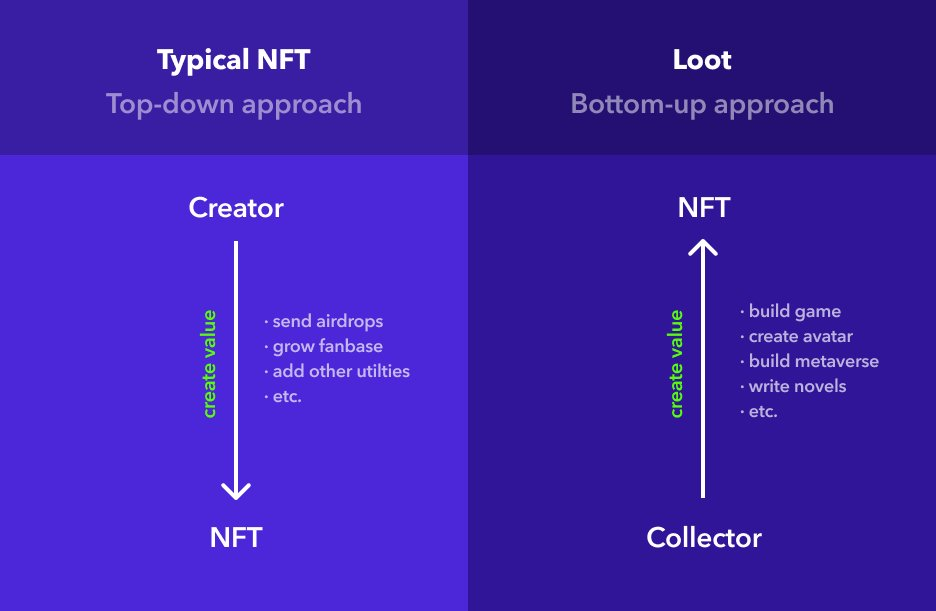

Web3 means a return to the network. Data is stored on blockchains, which are operated by the network of its users. This means that the ownership of the blockchain is distributed across its users. Scale that out far enough and the concept of measuring an individual’s level of ownership becomes abstract to the point that one could argue that the data on the blockchain is ownerless. This level of decentralization allows for the emergence of individual agency over the data they have custody over.

What makes the NFTs and tokens in your cryptowallet ‘yours’? Do you own them? Well… not really, the ownership is distributed across the blockchain. But you have custody over this data – you are uniquely in control, since you hold the keys to what happens to this data. This is why people warn about blockchains that are not sufficiently decentralized: you may have custody over your data, but a conglomerate of network operators could band together to seize ownership of it.

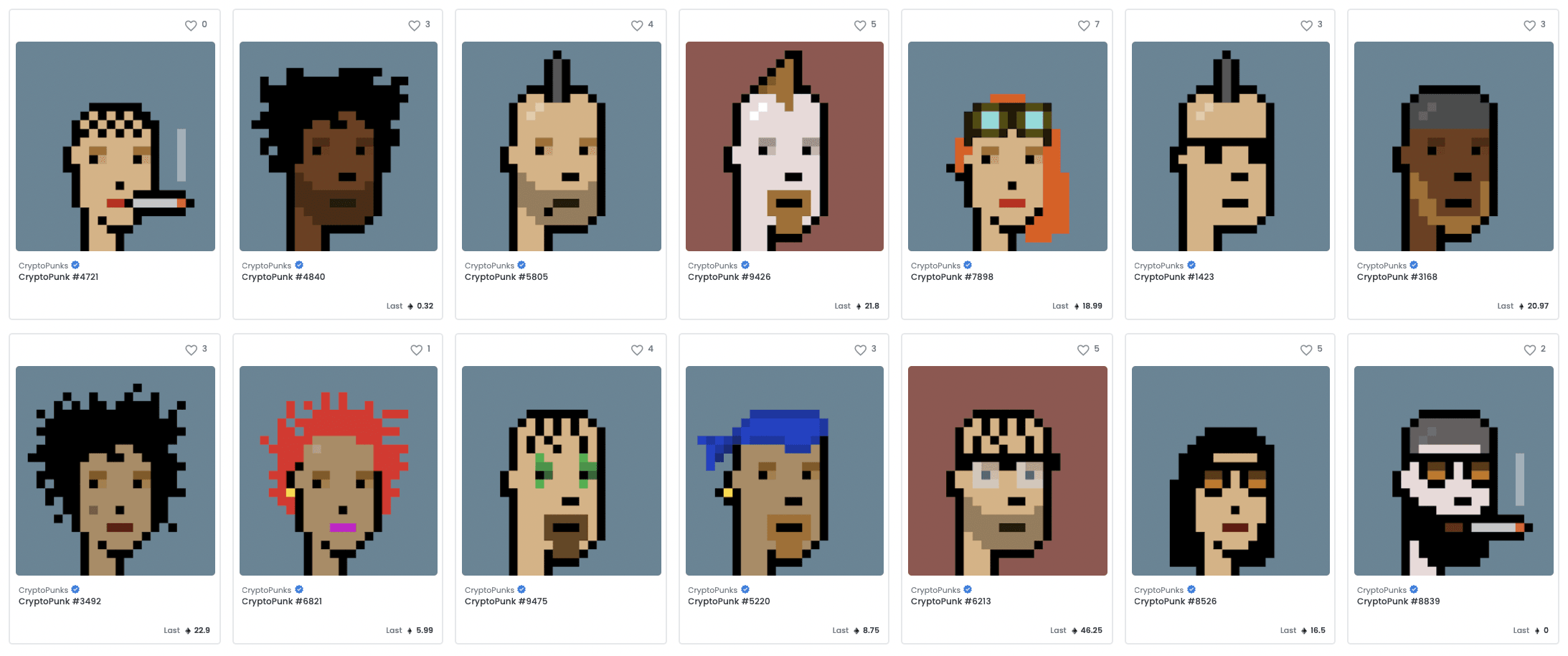

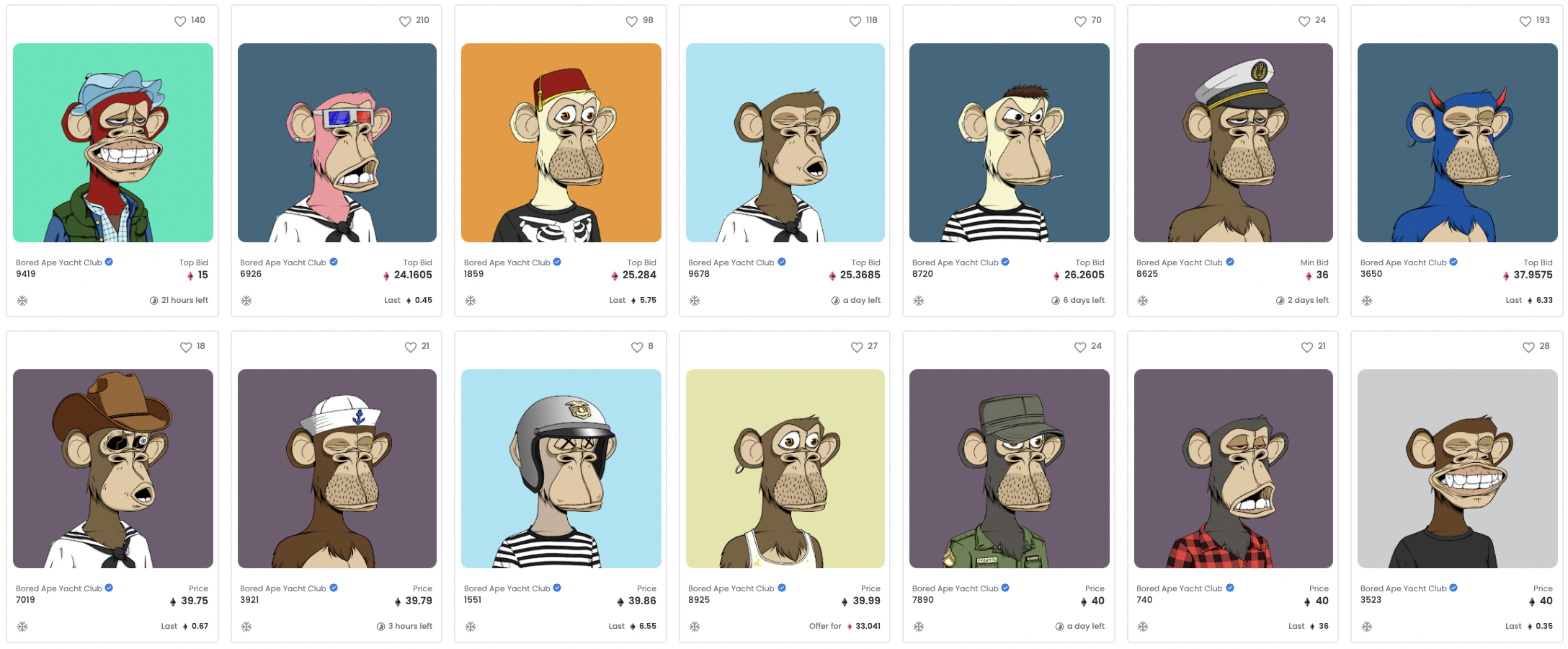

The reality of having a level of custody over your data to a degree that practically feels like ownership and that data being public and transparent creates a new reality to build in. New platforms can come along and tap into all the data that already exists. They don’t have to ask anyone for permission. Many blockchains, like Ethereum, are designed to be ‘permissionless’. As people build up their ‘on-chain’ profiles, they’ll place more importance on services that allow for interoperability for everything they’ve already collected. One example is the NFTs people spend money on: they value this data and platforms like Twitter & Instagram are mimicking web3 services by allowing folks to bring & display their NFTs inside the services.

This seems novel, but it’s been a de facto default for web3 services that are already years in the making. Snapshot, a governance tool for web3 organizations, allows anyone to connect their wallet, show that they have custody over certain tokens, and then allows them to participate in the respective communities’ votes. When the owner of popular NFT marketplace Hic Et Nunc took the platform down, the community scrambled to rebuild in record time. No important data was lost, because it was distributed on the network.

This creates a security mechanism: since the data is public and users hold the custody over it (as opposed to private & platform-owned), platforms that run afoul of their users’ best interests may see the community ‘fork’. That means they take their data & bring it elsewhere. The lack of interoperability has created a lock-in effect on users that is often leveraged to protect revenue and growth numbers. For example, if you leave a music streaming service, you lose access to all your playlists. If you leave a messaging app, you lose access to all your group chats & chat history. This is not the case with open standards like email, which you can access from multiple apps and services and even completely migrate to new service providers.

Web3 doesn’t lock-in like this (and if a ‘web3’ platform or blockchain does have this effect then it’s not ‘web3’ and you should think twice before spending your time or money there). Instead web3 services try to create long-term alignment with the users they cater to, since people can leave any time. This alignment takes the form of opening up participation in governance, as well as giving the users custody of the tools they use through tokens which can be used for governance, but often also come to represent the perceived value of a service (akin to shares, but without dividends).

Are the days of extractive platform economics behind us? Definitely not and I’d wager it will be a part of the internet’s economy for as long as we see the same extractive dynamics in other parts of our economies. But we do have the toolset to build things in fairer ways, almost like publicly governed and funded infrastructure – governed by the networks of people that make use of it.